Prefer to listen?

This blog post forms the basis of a podcast on our new coaching model, which you can listen to here.

But I Hear About The Kübler-Ross Change Curve All The Time! Is It a Myth?

Let’s Do A Bit of Background First

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross was a doctor who worked with people who were dying. She wrote a book around her experience and some observations about the emotions that surfaced for people when they knew they were dying. She referred to her model as ‘the stages of dying’. It’s now also been turned into stages of grief and transposed onto different scenarios relating to change.

What she observed is that people felt:

- some shock when people are told they’re dying

- then following that, there tended to be some form of denial

- And then potentially, they get angry

- Then they would go to a degree of bargaining

- Then they would generally move on to some depression around the fact that they weren’t going to be here anymore

- Then they would move on to some acceptance

- Finally, some decathexis, which is the letting go of emotions, emotional attachment for people around them.

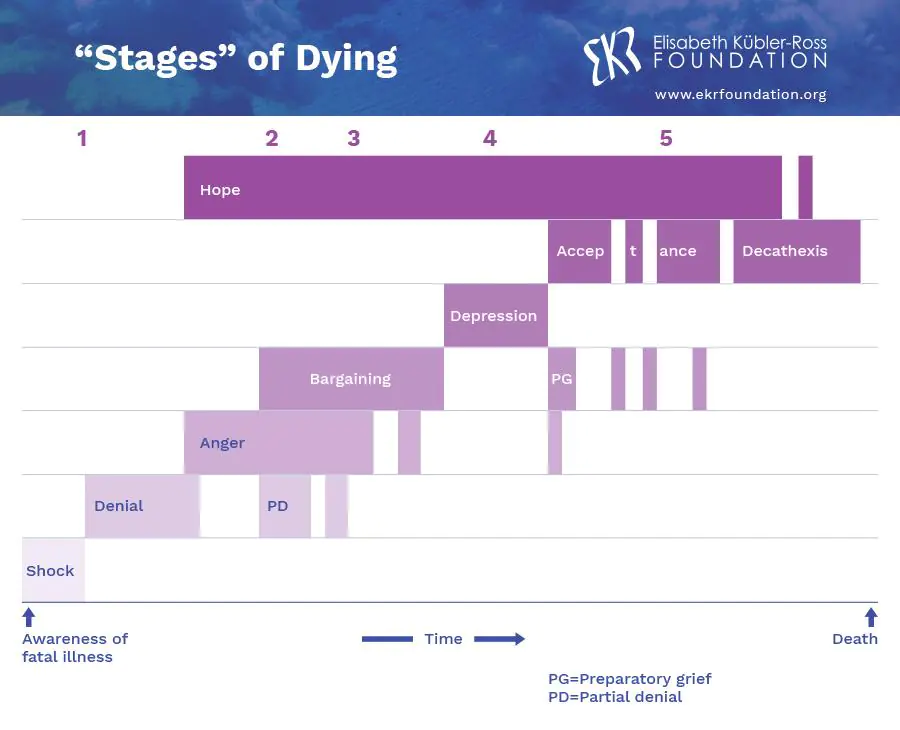

We’re presenting it as though always happens in this sequence, but Kübler-Ross acknowledges that things didn’t happen necessarily in this particular order. These are what she observed, and generally speaking, they came up in this order.

Within that, she also had other emotions mixed in. Hope was something that tended to exist almost throughout all of that experience.

In her book, Death and Dying, Kubler-Ross had a Gantt chart- like model (shown below). There would be a block of anger, but then there’s another bit of a block of anger later. That might come during acceptance. There might still be some anger, and then some denial might come back again later. It was all a lot messier.

If we think about that acceptance, whatever it is, whether it’s dying or the situation with COVID, there is a point at which we do become accustomed to it and just say, ‘Well, this is the new norm’.

If we think about COVID, it’s a great example where initially there were lots of emotional stuff going on, and then people got used to it and they learned how to deal with it. If you think back through your life, there have probably been lots of circumstances like that. We acclimatise and get used to it and that becomes the norm.

Tom was at a conference once where John McCarthy was speaking. John McCarthy was held hostage in Beirut for five years. Some of the time was in isolation, but then he was with two or three other people. He was writing about resilience at the time, so asked him the question, ‘How could you possibly stay resilient in such adverse conditions, terrible conditions. It wasn’t getting better day by day. It was just that was you where you were’. And he said, ‘Well, there were highs and lows. Actually, someone would say something that would make me laugh, and that would lift the day. There were peaks and troughs within that time’. He suggested that he just became accustomed to the way it was and settled into that. Not to say that it wasn’t a hideous experience, but he did just get used to it.

The Change Curve In Organisations

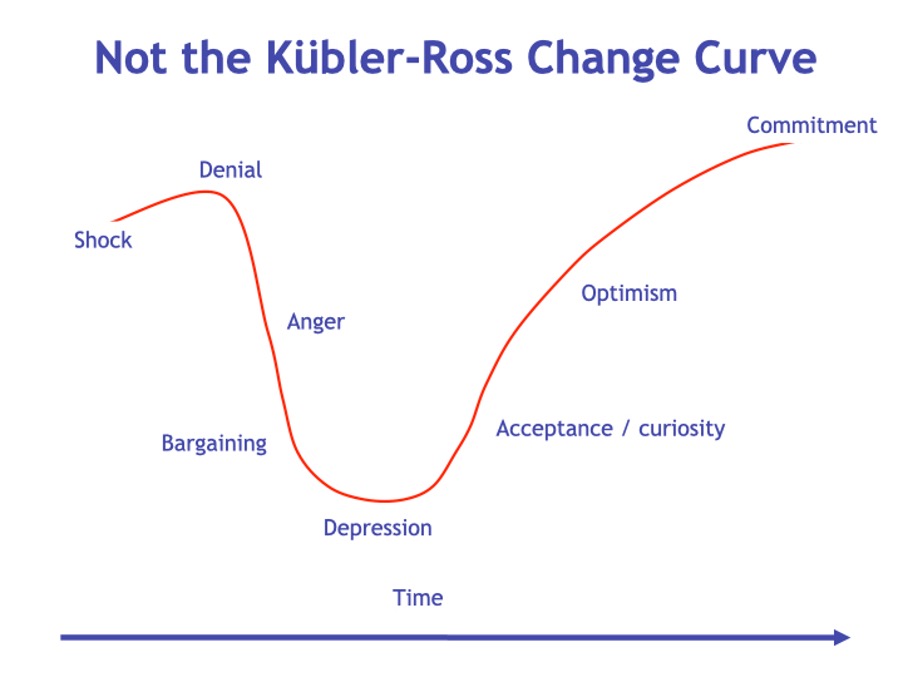

Obviously, all of that is very messy to present in a corporate environment. When people are going through change, organisations tend to present it very differently. They don’t want the messiness of it. There is some sense that when change happens, people are going to object. It’s going to mess with their heads a little bit, but over time, they will used to it. So they seem to have ironed it out to a more simplified version.

That’s why they roll out the change curve.

They like it to be a curve. They will have an initial spike of shock that actually for some people, might be quite exciting. There tends to be an uplift in people’s mood a little bit. Something’s happening. People are being made redundant. Then they realise it’s them. Then they go into the denial and then they get angry about it.

‘Well, it won’t happen to me, they’ve talked about this before. It’s never going to happen’, then when they know it’s definitely going to happen, it is them, then that anger comes up. But then generally, they get to that point of being sad about it all, of being fed up about it, but then getting to acceptance, and then they move on and go to a different organisation, potentially. So there is that sense that it could work as a change curve. But we all know that during lockdown, there wasn’t that gradual path, it was up and down all of the time. Lots of other emotions that came into it. You could feel okay one day, and then suddenly something, or even nothing, would make you suddenly feel a different way and you feel challenged by the situation.

It’s possible that the change curve exists because organisations want it to look like a smooth ride out. If you’re talking to managers who are going to have to manage change, it’s reassuring for them that eventually they will accept it. But it’s not necessarily true that everyone will accept it, some people stay angry. If people ignore that within an organisation, then they could be in for a rude awakening further down the line if the change hasn’t been managed successfully.

Feel The Fear

What’s interesting, going back to Elizabeth Kubler-Ross and her work, fear doesn’t figure in her stages of dying at all. She has a whole chapter in her book on the fear of dying, but then dismisses it, almost saying that whilst in the Western world, we have this fear of dying, we really shouldn’t have. She almost gets rid of that as an emotion that comes up for people so it doesn’t appear in her ‘stages of dying’. But it does appear for real people, and it will probably also appear for people when change is happening.

What does that mean in organisations? Are we all going to ignore the fear. Are we all going to ignore the messiness of change, and that for some people the anger doesn’t stop, or for some people the sadness doesn’t stop?

So the change curve is an oversimplification. We don’t think it was intended by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross to be used in the way it is today, so in that respect, it is a myth.

She never had a change curve.

Should we Not Use The Change Curve Then?

Of course you can use the change curve. If you are an organisation or a manager presenting change to people, then it might be an optimistic way to think about it. Helping people to understand that they will be going through the stages, through different emotions, and to normalise it and let them know they are going to work with and support them through that. That could be a nice way to present it.

We don’t think people shouldn’t use a change curve. But we wonder if they should recognise the origins of it, and how it was very messy, and there were other emotions involved as well.

But don’t talk about it being Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’, because she didn’t have one.

Be aware that models simplify things, they simplify life, and in this case, death, and change, and these things are simply not that simple.

Coaching is a really helpful way to support people through change. To find out more about our Doctors’ Transformational Coaching Diploma click through here